Always have an emergency planning

Early on with the COVID-19 situation, we saw signs of material shortages from reliable suppliers and an uptick in cases from dentists who had usually sent their work offshore; this was a clear indicator that something serious was taking place globally.

The pandemic brought to a halt the natural process of running a business and forced us to go into emergency mode. We stayed in close contact with our clients, kept abreast of the various stay-at-home measures in different states and then made decisions on a weekly basis, gradually reducing our workforce as demand lessened and then slowly bringing them back.

While this measured approach worked for us, there are things we wish we had in place that will become the cornerstone of our cohesive emergency plan currently under development. For example:

- More cross training so employees can step in where needed. Included in this would be training so that each department could operate independently - logging in cases, scheduling and invoicing, fielding questions from clients, and simply become smaller labs within the lab. If a future emergency required us to reduce staff, this would facilitate managing the workload and operating more efficiently.

- Client profiles updated once or twice a year with email addresses, phone numbers and alternative shipping addresses for offices and their key staff members so we can more quickly and easily get in touch.

- Better measures to assess risk regarding cases in production. In hindsight, when the pandemic hit, many of the cases in the lab should have been put on hold or cancelled and resumed only with new impressions when the offices re-opened. In some cases, the completed restorations didn’t fit properly because of the time lapse; in others, patients were out of work and couldn’t continue with treatment or the dentist closed or left the practice.

- We plan to share written policies with our clients regarding emergency production protocol, including a waiver of responsibility if cases are not seated within a reasonable amount of time from delivery.

- A scale-down business plan to direct operations during challenging times. We’re addressing marketing strategies and budgeting, taking into consideration the possible loss of work from customers in different geographic regions. We’re also defining how we’ll handle the potential need for reduction in our workforce as well as setting technicians up to work remotely or contracting with other laboratories to handle overflow.

- Other areas our plan will cover: credit protocols especially for customers with a bad payment history or those who traditionally run large balances; how to handle the lack of access to raw materials and other essential items during crisis; and resources like backup generators, water storage and more so the business can continue to function in an emergency.

Lower expenses and maintain the budget

The pandemic has forced us to look at our entire operation more critically in an effort to remain as agile as possible to not only survive the immediate crisis but come back in a better place. We began to analyze our costs more critically in order to pivot more of our fixed expenses to variable ones to reduce our overhead.

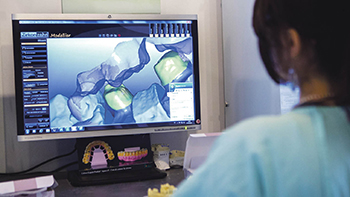

For example, pre-pandemic, no matter what our metal caseload looked like, we carried a $20,000 to $30,000 alloy inventory, plus the cost of equipment, maintenance and labor. Now we outsource all of this work to Argen. We also now outsource all of our restoration design to evident and the same concept applies: if the world shuts down again tomorrow and no work comes in the door, I don’t have these expenses.

We also tightened up our administrative and management structures. For example, we now outsource our human resources tasks to an outside company, and I lost my assistant—having one was great but a luxury I can’t sustain right now. Also, rather than five department managers, we now have one operations manager with team leads in each department.

In terms of production, when the work started coming in again, we brought back those who we felt were company-focused, motivated, efficient and versatile. Of course, these changes have meant a reduction in our workforce—we didn’t re-hire about 10% of our staff—and I don’t take that lightly; it’s been a really difficult but necessary decision.

The last thing that has made a difference is tracking our direct labor much more closely. For example, say we have two technicians who together can trim 300 dies in eight hours. If tomorrow we only have 220 to be trimmed, then they have a shorter day; if we have 320, we get a cross-trained technician from another area to jump in and handle the overflow to minimize overtime. We have gone from a direct labor percentage in the mid-30s—fully loaded with benefits—to the low-20s (although outsourcing our designs and metal work does account for a few of those percentage points). Our overall labor percentage—including administrative employees—went from the mid-50s to the high 30s, including benefits.

I think we’re a better company because of these changes. Looking back, we had become overweight and cumbersome; now I think we are the right size with the right crew. I expect this is our new normal.

Follow the right metrics

We have always tracked sales—the amount billed for work going out the door—but at the start of the pandemic, we realized the more important metric was one we weren’t looking at closely enough: the amount of work actually coming in.

With news of the shutdown looming, we knew our caseload was going to fall off and that layoffs were on the horizon. I love my employees and the idea of layoffs was terrifying; however, I knew if work came to a standstill we wouldn’t be able to pay them. I brought my managers together and asked, ‘how should we decide when to implement layoffs?’

We realized it didn’t make sense to base it on sales because—since that work is already done and out the door—we’d be making decisions five to 10 days behind. Instead, we focused on incoming workloads: how much there was and how long would it be in-house. Shifting our focus to the throughput—the number of units we would be moving through each department every day—helped us gain clarity.

With that perspective, we constructed our plan, defining three phases of layoffs using a standard deviation formula based on historical workloads. For example, phase one would begin when work was down 35% and administrative positions like our bookkeeper and customer experience manager would be laid off; by the time we hit phase 3, all but one technician would be laid off.

We sat with our employees and used a whiteboard to communicate the plan; we also let them know we were covering health insurance for two months and added a short-term disability plan in case they contracted the virus and couldn’t return to work. (Thanks to PPP funds, our entire staff was back to work within six weeks.)

This strategy of using a leading indicator (as opposed to a trailing indicator) has permanently changed the way we evaluate production; we stopped looking at it in terms of dollars sold and instead looked at what our system is producing. Now that we’re back up to speed—in fact, running 35% to 45% over our normal caseload—we’ve been able to make better decisions and become more efficient.

For example, looking at the number of units coming in the door—coupled with our own time study data—we realized it was taking longer than it should for cases to move through the lab. When we did the bottleneck analysis, we discovered that investing in additional training and hiring two highly experienced technicians in our removables department would allow us to complete work more quickly and increase production by 25% while still remaining profitable.

-Source: LMT Magazine-